Rain, hail or shine, Wagyu thrive

Thirty years of history has shown that Australian Fullblood Wagyu are pretty adaptable at coping with Australia’s weather extremes, but as our weather patterns change, it is important that they are given every opportunity to continue to thrive.

Anecdotally, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that Wagyu do well in northern Queensland right down to the cooler temperatures of Tasmania.

Classified as Bos taurus, along with other European breeds such as Angus and Hereford, the assumption is that Wagyu are not heat tolerant.

Many of the northern Wagyu pioneers crossed Fullbloods with Brahman in the belief it would enable the cattle to cope with the heat, and there is no doubt that introducing Bos Indicus has been beneficial.

Key points

Signs of Heat Stress

- Bunching or grouping under shade (if it is available)

- Excessive salivation

- Panting

- Open mouth breathing

- Less grazing and eating activity

- Increased water consumption

- Crowding around water resources

- Increased urination

- Refusal to lie down

Ridgeback TM at Darwin cattle yards

In an article published in 2018, US veterinarian Dr Jimmy Horner observed that:

“… most black Wagyu cattle are not impacted by heat stress until ambient temperatures reach 75°F (24 °C) or the “Heat Index” is above 80. Japanese Brown Wagyu (Akaushi) cattle appear to be able to tolerate slightly higher temperatures than black Wagyu which likely explains the fact that most of these cattle are located primarily in southern Japan which is more tropical than northern regions and temperatures can reach well above 100°F (38°C) with 60% plus relative humidity during summer months…”

Dr Horner readily admits that his thoughts are speculative, but did explain that he believed that the extreme variation in Japan’s climate could have contributed to this inherent ability as well. By traversing the ranges of the environmental spectrum in Japan, one can go from a somewhat frigid climate all the way to a more tropical environment such as Kyushu (southern Japan).

The sentiment is echoed by Australian feedlotters specialising in Wagyu, who have noted that Wagyu are more resilient in the heat.

Changing weather patterns

Most generational farmers around the country would be aware that over the years the seasons have changed; droughts bite harder and floods are more inundating.

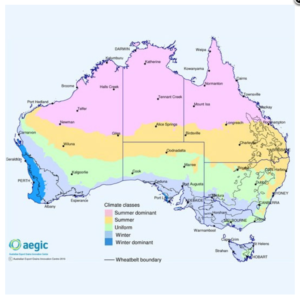

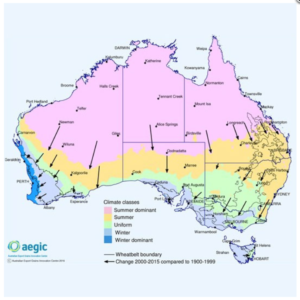

In 2016 a study was conducted by the Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre to map seasonal rainfall zones and the changes in a 15 year period. Utilising data from the BoM, the period 1990-1999 in Figure 1a, shows the typical rainfall of the day. In the period 2000-2015 it is evident that the lower rainfall zones of northern Australia have shifted southward, highlighted by the orange band that now extends into southern Queensland and northern NSW, reducing winter rainfall by as much as 10-30%.

As temperatures increase in the tropics, the further the hot air reaches away from the equator with increased evaporation, clear skies and stability. Termed the Hadley Cell, the high pressure system generated is coincident with sub-tropical deserts, including Australia’s. A further consequence of this broadening higher pressure is an inability for cold fronts from the south to push further up the continent.

The flow on effects for southern Australia include shorter winter months for rain, and hot and drier summers which impact on pasture and rangelands as well as heat and water stress for livestock.

Long term strategies to help cattle cope

Feedlots

Accredited feedlots in Australia must abide by the National Feedlot Accreditation Scheme, which outlines the care and management of cattle. Animal welfare of cattle in the feedlot require that shade be available for hot weather, good drainage for wet weather to avoid foot problems and the use of water spraying to keep dust down.

Professor Richard Eckard, a climate specialist for livestock at University of Melbourne, says that caution should be taken with water spraying as it can raise the level of humidity, if incorrectly applied, within a feedlot environment. With much of his research surrounding dairy cattle, Dr Eckard believes there is many lessons to be learned from that industry, including monitoring of milk production in cattle as an indication of stress due to weather patterns. Milk production in dairy cattle decreases noticeably when animals are under heat or cold stress.

“One of the scenarios for the near future in the inland dairy industry is the ratio of cattle in confinement feeding systems compared to grazed pasture,” said Dr Eckard. “Cattle may be shedded more often in sheds that are cooled or equipped with fans, in these hotter inland regions, while irrigation water is reserved for when pasture is best able to utilise it, rather than flood irrigation in the summer months.”

According to Dr Eckard, it is not just the day time heat that can cause heat stress, but if it does not cool down sufficiently overnight, cattle struggle to offload the cumulative effects of daytime heat. An overnight temperature in the order of 21 °C or less will enable cattle to cope better with the heat.

On-farm

Reproduction and calving in hot conditions need to be handled with care – minimise time for cattle handling, make sure the insemination process is as efficient as possible and aim for calving to be in the cooler months, away from the extremes of Summer (or Winter).

When it comes to feed and rations, Dr Horner recommends that cattle be fed more rations in the cool of evening, to reduce the metabolic heat load through the heat of the day. High quality forage or pasture during summer also reduces heat load as they are easier to digest.

2 - 2Shares